1. Introduction

1.1. Why do we need GD?

We can easily find the prediction function from a given dataset using the formula of linear regression:

However, since it involves an inverse function, it is manageable with small datasets and low dimensions, but when dealing with larger datasets and higher dimensions, it consumes a lot of computational resources. Therefore, we need to use Gradient Descent, a classic yet very popular algorithm today.

Or when finding the extremum of a function, the equation cannot be solved easily. In this case, we can use the gradient descent algorithm to find an approximate solution.

1.2 Method

Gradient Descent is a first-order iterative optimization algorithm for finding a local extremum of a differentiable function. To find a local minimum of a function using gradient descent, one takes steps proportional to the negative of the gradient (or approximate gradient) of the function at the current point. Conversely, taking steps proportional to the positive of the gradient leads to finding a local maximum; this method is called gradient ascent.

More specifically, GD repeatedly changes the value of so that in each iteration, it is hoped that becomes smaller and approaches the minimum.

The way to adjust and ensure decreases is to set to a negative portion of the gradient: , where is a positive number called the learning rate. Finally, we get:

According to Figure 1, at point we have , which means the value of will increase or move to the right, causing the value of to gradually decrease towards the minimum.

Figure 1: Gradient Descent Diagram

2. Gradient Descent and Linear Regression.

Now let's go through the concept of matrix derivatives (to work with multi-dimensional data) and numerical differentiation (to calculate the approximate gradient at a specific value of ).

2.1 Matrix Derivatives

In the previous example, was just a one-dimensional vector, but in reality, the problems presented can also have as a vector in -dimensional space.

In linear regression, is a vector, and its derivative formula is:

2.2 Numerical Differentiation

According to numerical differentiation, we can calculate the derivative according to (3) with a small error compared to the normal formula (2).

We will use it to check if we have calculated the derivative correctly.

You can read more here: Numerical Differentiation - Wikipedia

2.3 Simulation with Python

Summarizing the Linear Regression problem. First, consider the following two sets:

We need to find and to have the equation:

In other words:

But there are no that satisfy creating a line passing through all the data points, so we will find such that:

The derivative of (5) with respect to is:

Figure 2: Gradient Descent Animation

from matplotlib import animation

from matplotlib.animation import writers

import numpy as np

import matplotlib

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from sklearn import linear_model

def cost(x):

m = A.shape[0]

return 0.5/m * np.linalg.norm(A.dot(x) - b, 2)**2

def grad(x):

m = A.shape[0]

return 1/m * A.T.dot(A.dot(x) - b)

def numerical_grad(x):

eps = 1e-4

g = np.zeros_like(x)

for i in range(len(x)):

x1 = x.copy()

x2 = x.copy()

x1[i] += eps

x2[i] -= eps

g[i] = (cost(x1) - cost(x2))/(2*eps)

return g

def check_grad(x):

x = np.random.rand(x.shape[0], x.shape[1])

grad1 = grad(x)

grad2 = numerical_grad(x)

if np.linalg.norm(grad1 - grad2) > 1e-5:

print("Check grad function!")

return

def gradient_descent(x_init, learning_rate, iteration):

x_list = [x_init]

for i in range(iteration):

x_new = x_list[-1] - learning_rate*grad(x_list[-1])

if np.linalg.norm(grad(x_new))/len(x_init) < 1e-3:

break

x_list.append(x_new)

return x_list

A = [2,9,7,9,11,16,25,23,22,29,29,35,37,40,46]

A = np.array([A]).T # Ox

b = [2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16]

b = np.array([b]).T # Oy

# Draw data

fig1 = plt.figure("GD for Linear Regression")

ax = plt.axes(xlim=(-10,60), ylim=(0, 20))

plt.plot(A, b, 'ro')

# Linear Regression

lr = linear_model.LinearRegression()

lr.fit(A,b)

x0_gd = np.linspace(1,46,2)

y0_sklearn = lr.intercept_[0] + lr.coef_[0][0]*x0_gd

plt.plot(x0_gd, y0_sklearn, color="green")

# Add one to A

ones = np.ones((A.shape[0], 1), dtype=np.int8)

A = np.concatenate((ones, A), axis=1)

# Random and plot initial line

x_init = np.array([[1.], [2.]]) # (a, b)

y0_init = x_init[0][0] + x_init[1][0]*x0_gd # y = a + bx

plt.plot(x0_gd, y0_init, color="black")

# check grad

check_grad(x_init)

# Run

iteration = 100

learning_rate = 0.0001

x_list = gradient_descent(x_init, learning_rate, iteration)

for i in range(len(x_list)):

y0_gd = x_list[i][0] + x_list[i][1]*x0_gd

plt.plot(x0_gd, y0_gd, color="black", alpha=0.3)

line , = ax.plot([],[], color="blue")

def update(i):

plt.xlabel('Iteration: {} Learning rate: {}'.format(len(x_list) - 1, learning_rate))

y0_gd = x_list[i][0][0] + x_list[i][1][0]*x0_gd

line.set_data(x0_gd, y0_gd)

return line,

iters = np.arange(0,len(x_list), 1)

plt.legend(('Data', 'Solution by Linear Regression', 'Initial Line For GD'), loc=(0.48, 0.01))

plt.title("Gradient Descent")

line_ani = animation.FuncAnimation(fig1, update, iters, interval=50, blit=True)

plt.show()

3. Going into more detail

3.1 When to stop?

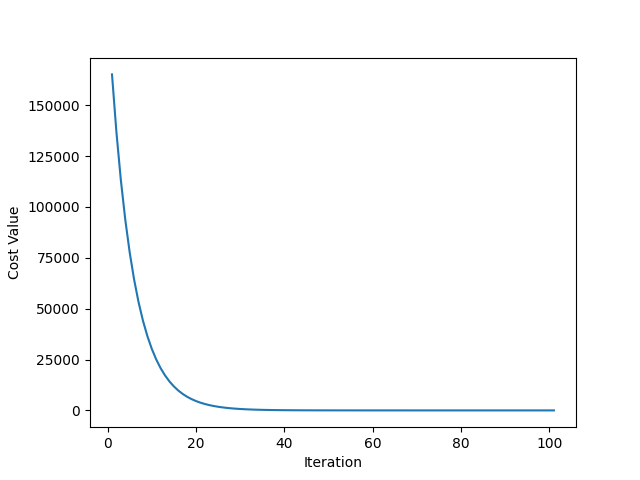

The relationship between the number of changes in (Iteration) and the value of (Cost Value) Figure 3.1. It is easy to see that the Cost Value tends to approach and remains stable after iteration 50. Repeating the remaining iterations does not seem to reduce the Cost Value much and may not be necessary.

Based on this, we can come up with a good threshold to stop the GD function.

Figure 3.1: The relationship between cost and iteration

Figure 3.2: Case or quadratic function (Parabolic)

Figure 3.2 shows that when the threshold of the gradient value is around ( ), we get a relatively good result compared to the result from Linear Regression.

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.animation as animation

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from matplotlib.animation import writers

def cost(x):

m = A.shape[0]

return 0.5/m * np.linalg.norm(A.dot(x) - b)**2

def grad(x):

m = A.shape[0]

return 1/m * A.T.dot(A.dot(x) - b) # return f'(x):[a, b, c].T

def numerical_grad(x):

eps = 1e-4

g = np.zeros_like(x)

for i in range(len(x)):

x1 = x.copy()

x2 = x.copy()

x1[i] += eps

x2[i] -= eps

g[i] = (cost(x1) - cost(x2))/(2*eps)

return g

def check_grad(x):

g1 = grad(x)

g2 = numerical_grad(x)

if np.linalg.norm(g1 - g2) > 1e-5:

print("Check grad function")

return

def gradient_descent(x_random, learning_rate, iteration):

x_list = [x_random]

for i in range(iteration):

x_new = x_list[-1] - learning_rate*grad(x_list[-1])

if np.linalg.norm(grad(x_new))/len(x_gd) < 0.03:

break

x_list.append(x_new)

return x_list

b = [2,5,7,9,11,16,19,23,22,29,29,35,37,40,46,42,39,31,30,28,20,15,10,6]

b = np.array([b]).T

A = [2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25]

x_gd = np.linspace(1,46,10000)

# x_random = np.random.rand(3, 1)

# print(x_random)

x_random = np.array([[ -2.1],

[ 5.1],

[-2.1]])

fig1 = plt.figure("GD for Linear Regression")

ax = plt.axes(xlim=(-5,30), ylim=(-5, 50))

A = np.array([A]).T

plt.plot(A,b, 'ro')

# add ones and col 3 to A

ones = np.ones((A.shape[0], 1), dtype=np.int8)

col_3 = A*A

A = np.concatenate((ones, A, col_3), axis=1)

# Linear Regression

x_lg = np.linalg.inv(A.T.dot(A)).dot(A.T.dot(b))

y_lg = x_lg[0][0] + x_lg[1][0]*x_gd + x_lg[2][0]*x_gd*x_gd

plt.plot(x_gd, y_lg, color="green")

# Plot random

y_random = x_random[0][0] + x_random[1][0]*x_gd + x_random[2][0]*x_gd*x_gd

plt.plot(x_gd, y_random, color="black")

# check grad

check_grad(x_random)

iteration = 70

learning_rate = 0.000001

x_list = gradient_descent(x_random, learning_rate, iteration)

for i in range(len(x_list)):

y0_gd = x_list[i][0] + x_list[i][1]*x_gd + x_list[i][2]*x_gd*x_gd

plt.plot(x_gd, y0_gd, color="black", alpha=0.3)

# Draw animation

line , = ax.plot([],[], color="blue")

def update(i):

y0_gd = x_list[i][0][0] + x_list[i][1][0]*x_gd + x_list[i][2][0]*x_gd*x_gd

line.set_data(x_gd, y0_gd)

return line,

iters = np.arange(0,len(x_list), 1)

# Legend for plot

plt.xlabel('Iteration: {} Learning rate: {} |Grad| = {}'.format(len(x_list) - 1, learning_rate, np.linalg.norm(grad(x_list[-1]))/len(x_gd)))

plt.legend(('Data', 'Solution by Linear Regression', 'Initial Line For GD'), loc=(0.48, 0.01))

plt.title("Gradient Descent")

line_ani = animation.FuncAnimation(fig1, update, iters, interval=50, blit=True)

# Save animation to gif file

# Writer = writers['ffmpeg']

# writer = Writer(fps=15, metadata={'artist': 'Me'}, bitrate=1800)

# line_ani.save('GA Animation.gif', writer)

# fig2 = plt.figure()

# print(len(x_list))

# cost_list = []

# iteration_list = []

# plt.xlabel("Iteration")

# plt.ylabel("Cost Value")

# for i in range(len(x_list)):

# iteration_list.append(i+1)

# cost_list.append(cost(x_list[i]))

# plt.plot(iteration_list, cost_list)

plt.show()

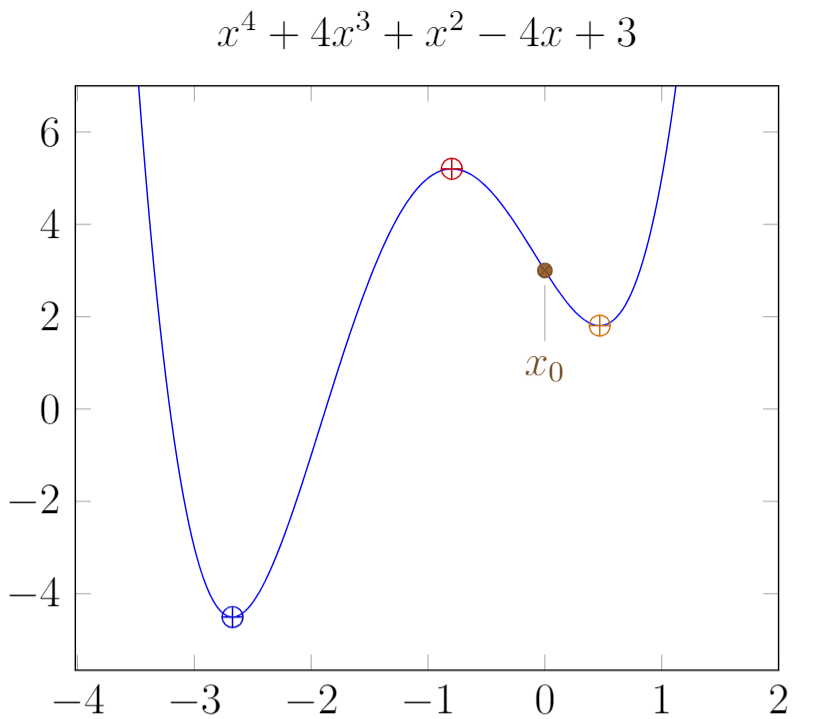

3.2. Stuck at local minima

When randomly initializing and running, as mentioned above, there will be many local minima. Random initialization can cause us to get stuck at local minima, not the global minimum, as shown in Figure 4, resulting in a non-optimal solution. When working with higher-dimensional spaces, there are even more local minima.

Figure 4: Stuck at local minima

3.3. Learning Rate

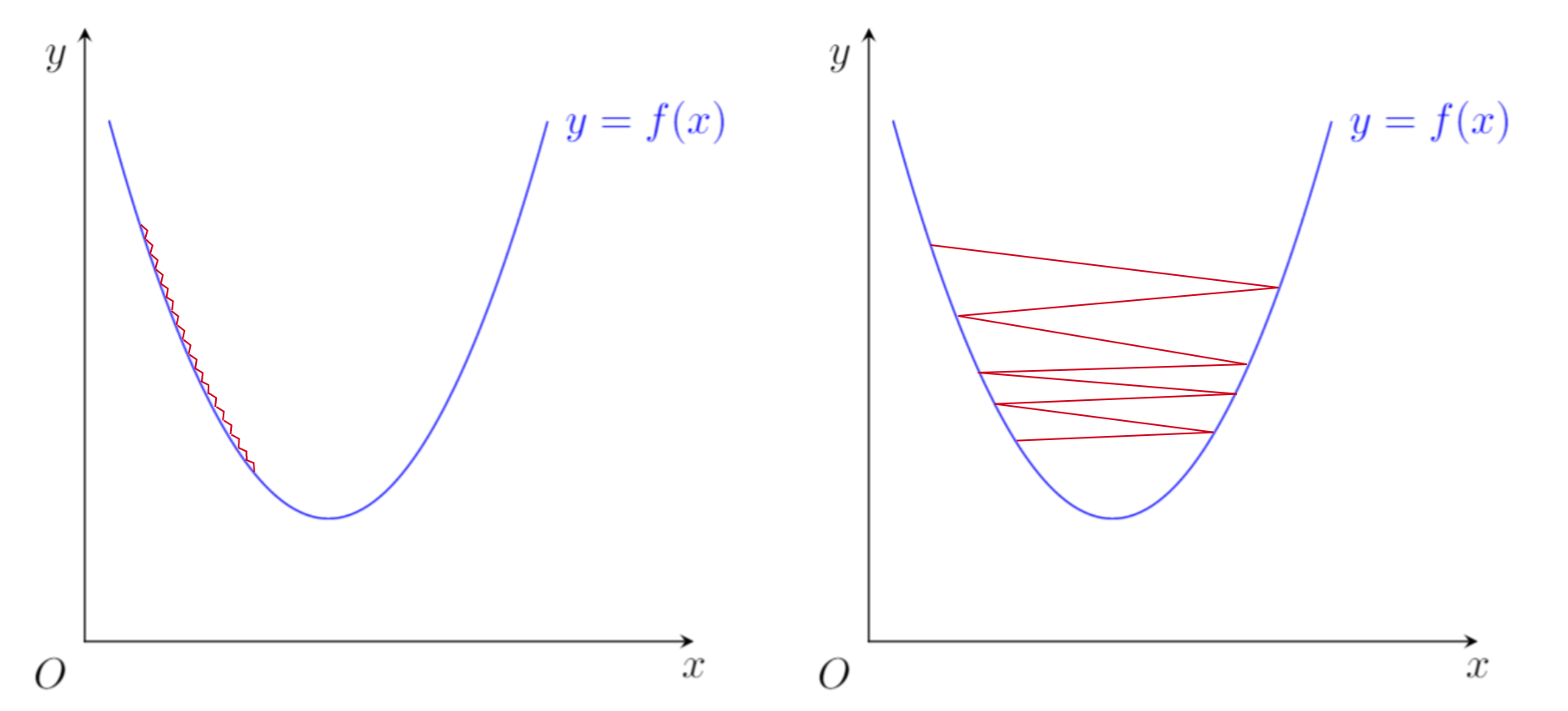

The learning rate () is a very important parameter. A small as in Figure 5 can slow down GD and make it very slow to converge. On the other hand, a large as in Figure 5 can make GD unable to converge.

Figure 5: Learning Rate (left: small , right: big )

4. Conclusion

Gradient Descent is a very popular and powerful optimization method. It can help us find the extrema of a function quickly and efficiently. However, choosing the learning rate and the initial point is an important issue that needs to be carefully considered.